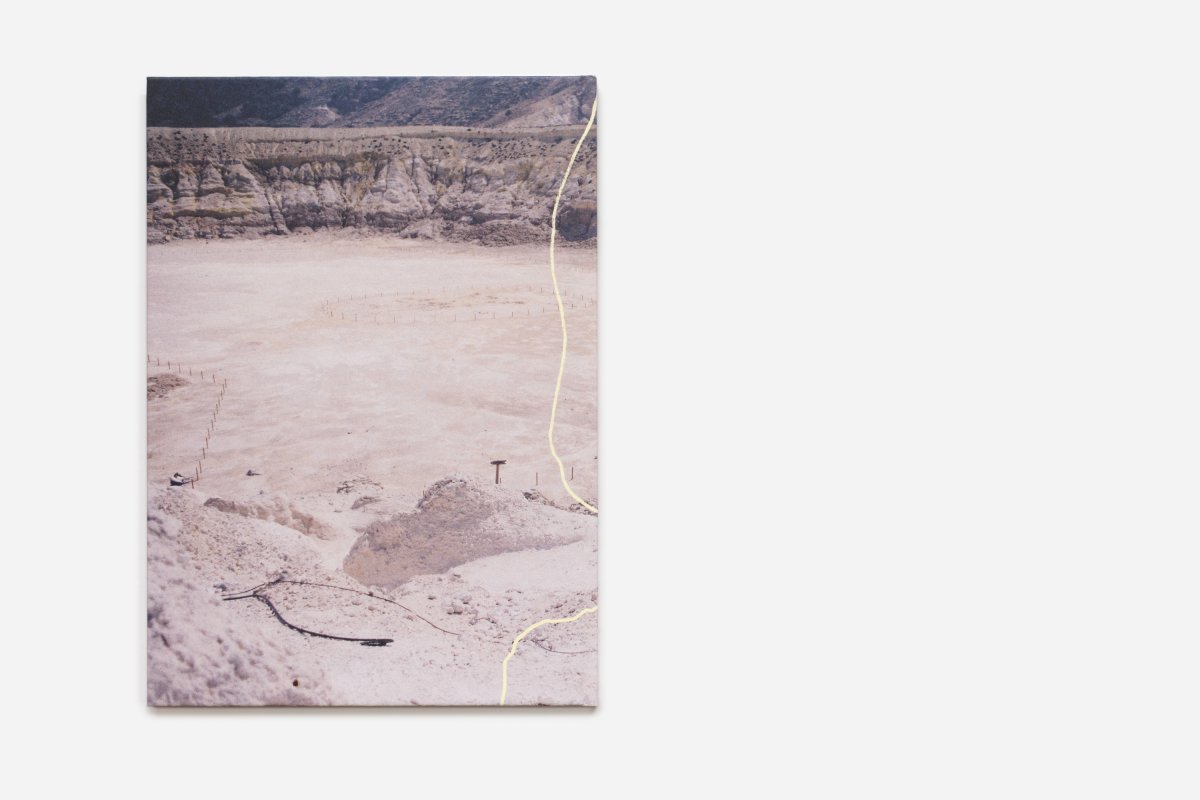

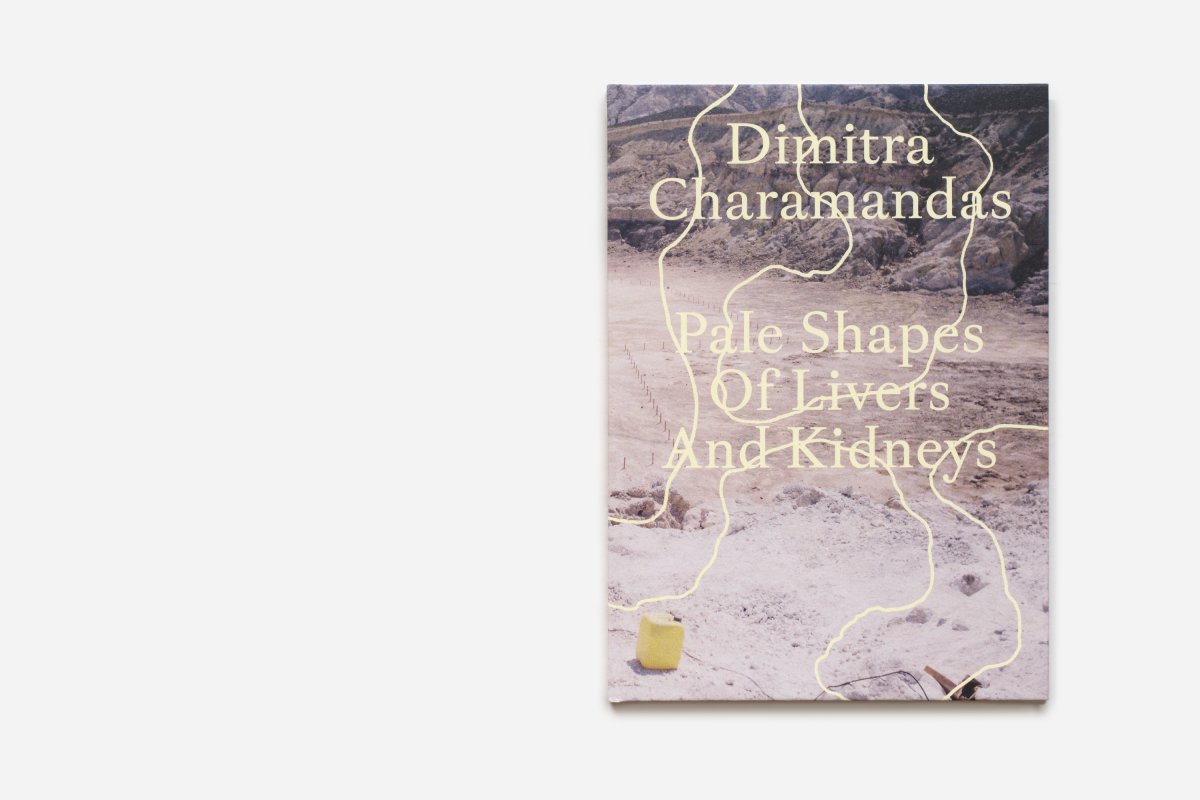

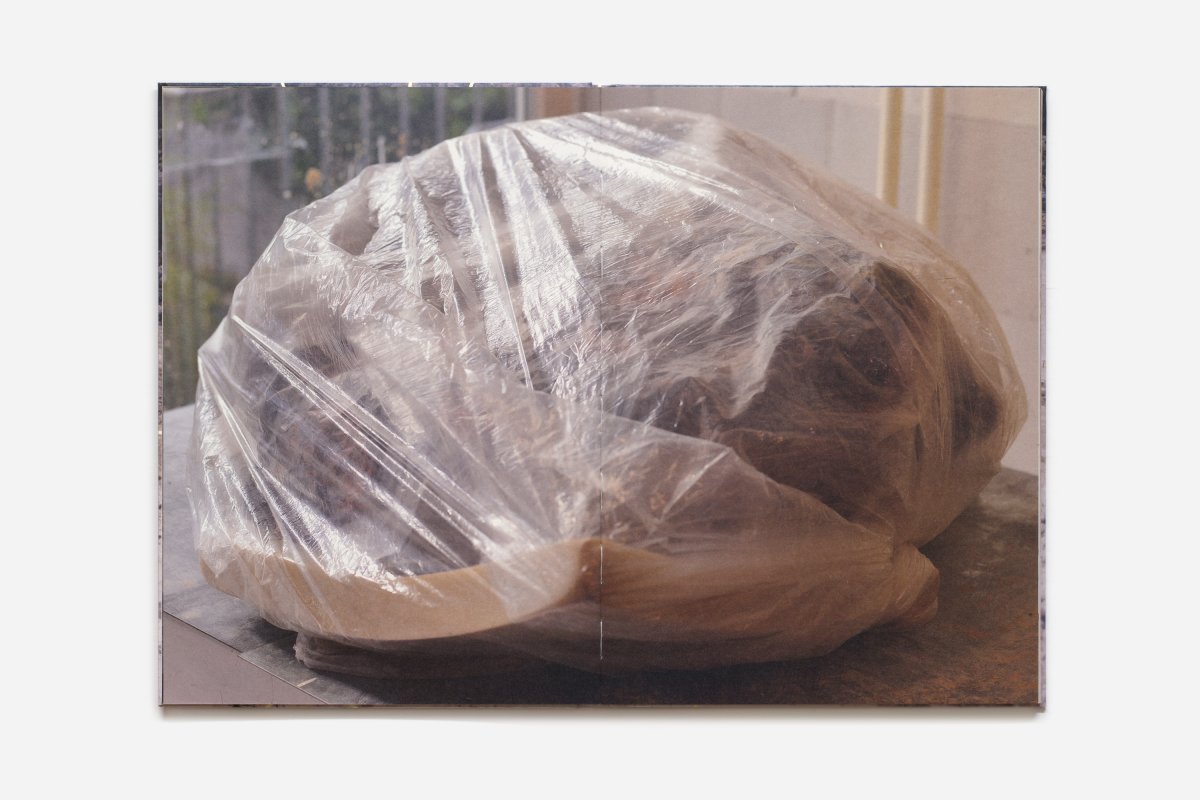

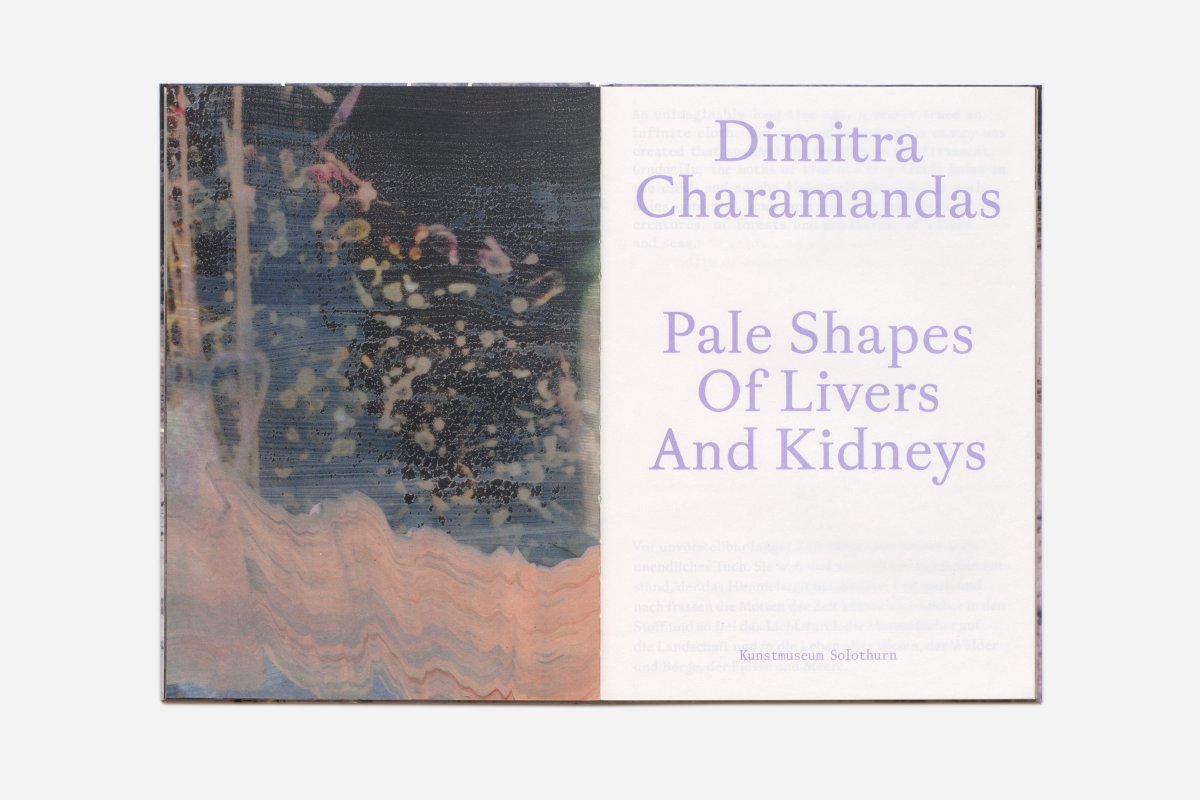

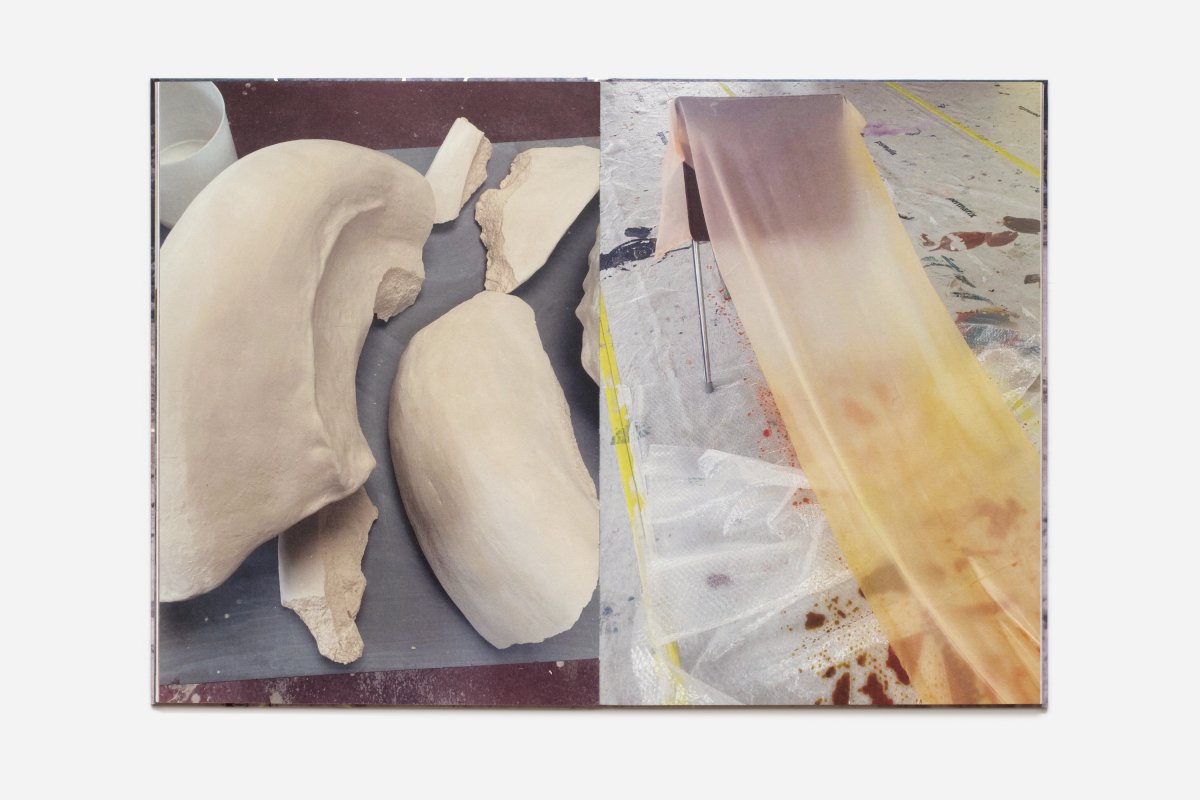

Pale Shapes Of Livers And Kidneys, Publication, 2023

Pale Shapes Of Livers And Kidneys, 18 x 25 cm, 80 pages, offset print, Lessebo and Daunendruck paper, hardcover, bound, edition of 450 copies, published by Kunstmuseum Solothurn

textWhen I don’t know where to start, I always start from the body, my most intimate navigation tool. Picture me floating belly-up in the mothering, dark blue waters, embraced by mountainsides. My hands are stretched behind my head, while my legs form the Greek letter lambda (Λ). The gulf fills the contours of my body, we are fused in a continuum of water.

Swimming came before fear. Let go and the water will carry you as you carry it within you. A simple reminder that your body consists of more than half of water. Shape your hands and legs like the English letter “c” that terribly wants to become an “o” and gently push the water to propel you forward. Make the perfect circle by making two imperfect halves with your legs as you push the water behind you.

In Greek, the word for gulf is “kólpos,” a masculine noun. It refers to a formation of the coastline or an inlet of an ocean or sea. It is also associated with various cavities in the body, such as the vagina and the space between the arms, symbolizing an embrace. Here, bodies and landscapes are interchangeable, sharing a distinct psychogeography. The gulf represents a sense of secure attachment, like an ideal caregiver always ready to embrace you.

The first mirror is the water, reflecting our perspectives of the gulf from opposite sides. I find myself on an almost-island, resembling a leaf in the south, while you overlook the same waters from the north. The Corinthian Gulf bridges our distance, appeasing our separation. To reach you, I cross the Isthmus bridge, traversing towards the ancient divination city of Delphi, the belly button of the world, where the future was said to be hidden safely within the earth’s bowels.

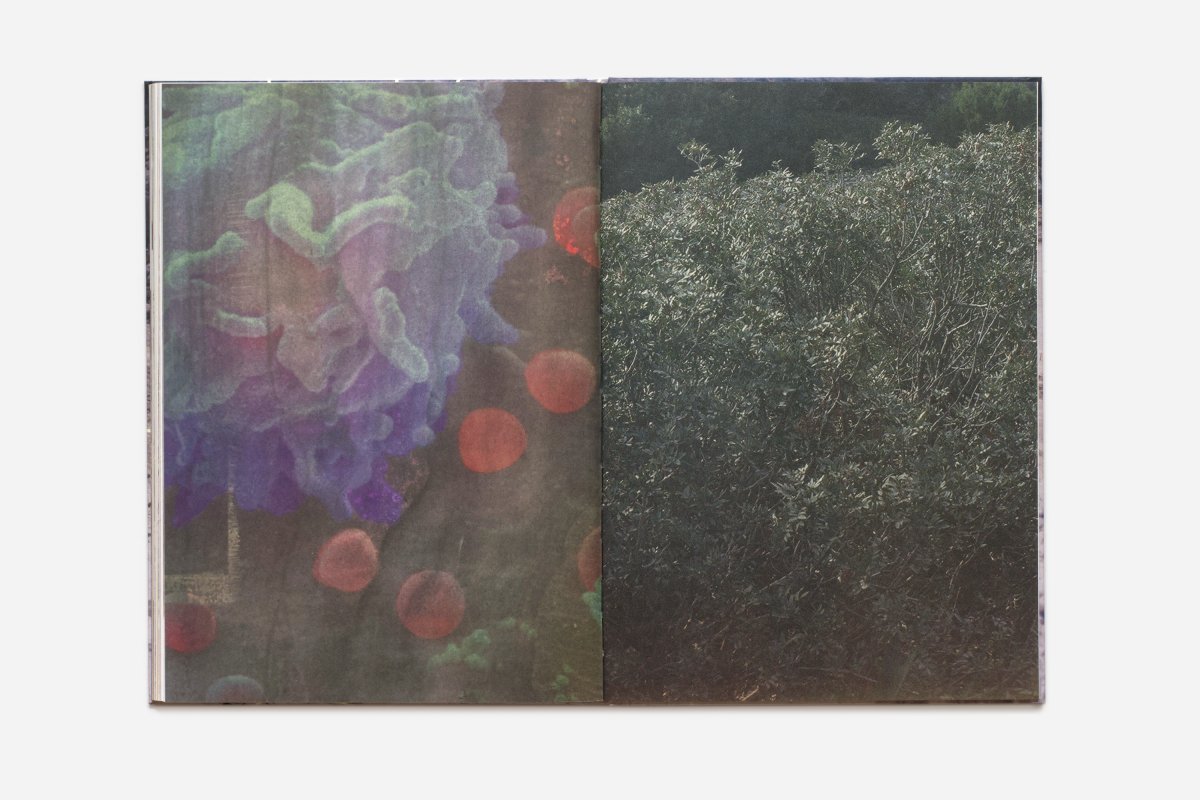

Today, machines excavate the terracotta colored soil. Reminiscent of Roman roof tiles from typical provincial houses in Greece, the red-colored earth traditionally symbolizes fertility, potentiality, and safety. Yet here it is toxic industrial waste from an aluminum production plant, covering 17% of the seabed.

Covered in sweat, I dive in to cool down at Galaxidi. I stand on the edge of the concrete platform with my legs slightly bent and stretch out my arms, aiming for the water. Submerging a few centimeters below, I feel a sharp sting—the touch of a Pelagia noctiluca, a non-indigenous purple jellyfish. How can a body made of 98% water hurt so much?

The inviting surface of the water contrasts with the burning sensation of my skin. It is the red mud on the seabed and the stream of warm water from the gas-fired power plant that create an incubator for jellyfish. Alien marine species introduced through ships’ ballast water add to the complexity of shifting waters in the gulf. In this strange new environment, marine organisms assert their presence with teeth and tentacles, claiming their newfound home. Perhaps all water is foreign, brought by a shower of asteroids millions of years ago. Yet the lingering sting leaves me unsure of where I am most safe and where I am most vulnerable.

Water to water, I wonder: how can we continue to carry each other?

Eleni Riga, Letter From the Gulf

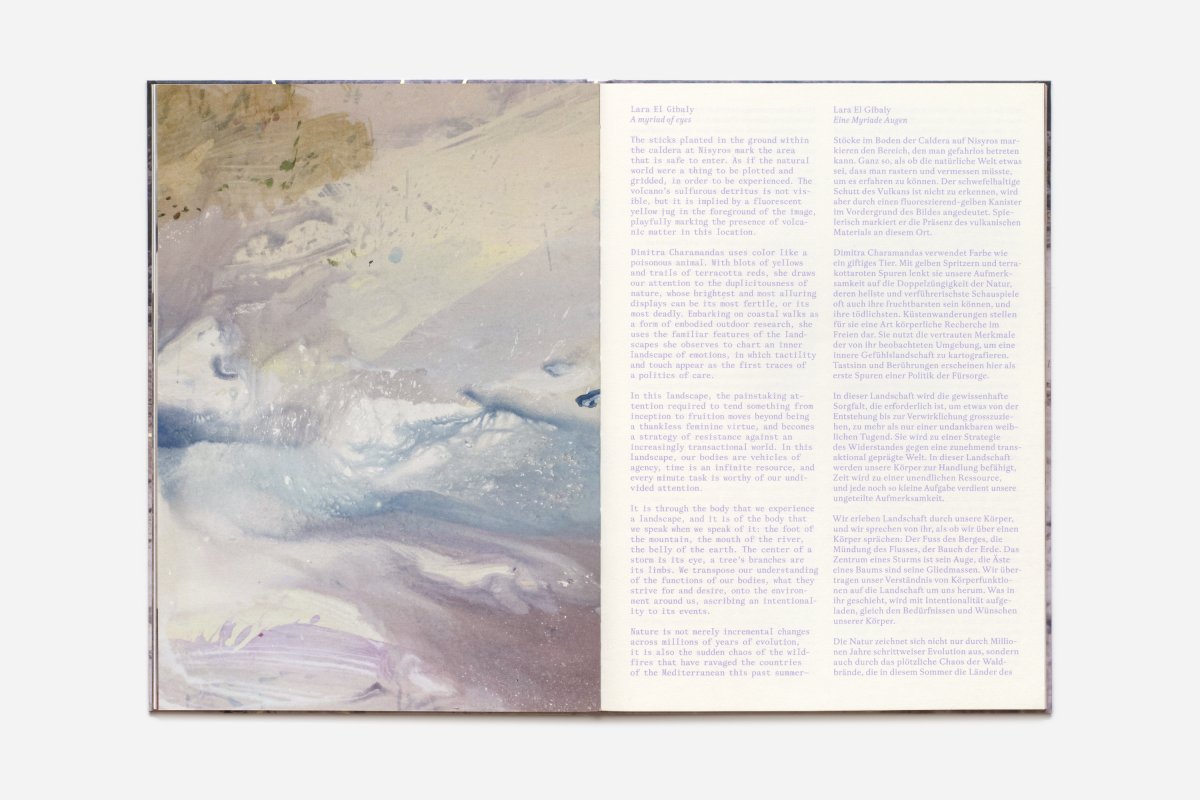

The publication Pale Shapes Of Livers And Kidneys accompanied the exhibition Tides at Kunstmuseum Solothurn (fall 2023). It holds a collection of text fragments and imagery around the processes leading up to the exhibition. With contributions by Lara El Gibaly and Eleni Riga. Developed in close exchange with curator Meret Kaufmann. Graphic design by Martina Meier, Bureau Mia, Zurich, published by Kunstmuseum Solothurn.

The ground is strangely soft. It yields to steps, absorbs the world’s noise. It creates a bubble, a temporary vacuum in the middle of the island where the landscape turned itself inside out. In the absence of sound, awareness turns inward. A constant rush of blood accompanies my breathing and the palpitations of my heart. Suddenly I sense a high-pitched note, a sharp tone of alert.

Text fragments from the publication Pale Shapes of Livers And Kidneys

Slender black snakes wriggle in night waters, glide beneath me in silence. I am a pale stain in dark water, shiny petroleum. I try to maintain my state of suspension so as not to disturb them. They do not attack; they whisper voiceless riddles.

The perspective shifts. Now I gaze up from the seabed at my own body afloat, below it the swarm of snakes, articulating question and exclamation marks, circles, long dashes and loops of infinity. They glide through the water, probing hollows and clefts in the rocks, liquid cracks in black glass.

A dead moray eel floats five fingerbreadths below the glittering surface, upside down, powerless jaw agape.

Late in the day, the arsenic-coloured lake turns kyparissi, the colour of cypresses. The moon paints pale dots, pale shapes of livers and kidneys.